Following her death in 1954 and under the instruction of her husband, Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo’s possessions were locked away in La Casa Azul, her lifelong home in Mexico City. Half a century later in 2004, the house was re-opened and her collection of clothing, photos, jewellery, cosmetics, letters and other personal items were discovered. This has all been put on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the exhibition is running until the 4th November.

Hilda Trujillo, Director of the Museo Frida Kahlo, upon opening the house “I felt like an intruder, for what right do I have to be there with Frida’s things? At times I thought I wasn’t entitled to do this, that no-one was. However, it was also important to restore, rescue […] the letters and photographs – had been left as they were, frozen in time – but they were in very bad condition.”

Frida Kahlo suffered from poor health throughout her life. At age 6 she contracted polio, causing her right leg and foot to grow thinner than her left one. Tragedy then struck again at the age of 18, Kahlo and her then boyfriend were travelling home on a wooden bus when it collided with a street car. The accident killed several people and fractured her ribs, both her legs, and her collarbone. An iron handrail impaled her through her pelvis, fracturing the pelvic bone. It took her several months to recover, 3 of which were spent wearing a cast around her rib cage. Lying in bed, she took up painting on a modified easel and mostly painted self portraits. She stated “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best”.

The polio she suffered from at a young age, combined with her accident at 18, would leave Kahlo limping and she would often wear traditional long skirts to cover that for the rest of her life. Distinctive and colourful indigenous Mexican garments such as cotton huipils (loose fitting tunic) with beautiful embroidery and stitching are on display at the exhibition and some of Frida’s personal clothing still have flecks of paint on them! Wearing traditional dresses allowed Kahlo to emphasise her ancestry and her profound interest in its culture remained important facets of her art throughout the rest of her life.

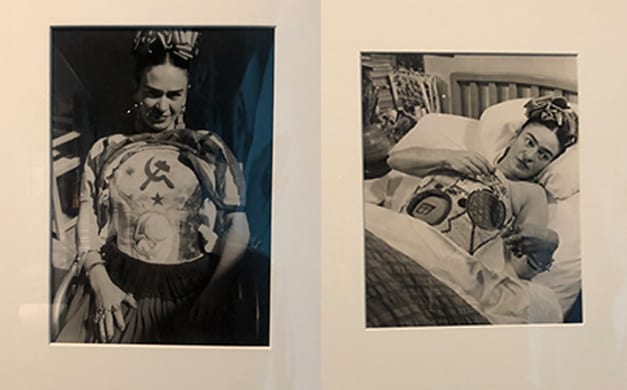

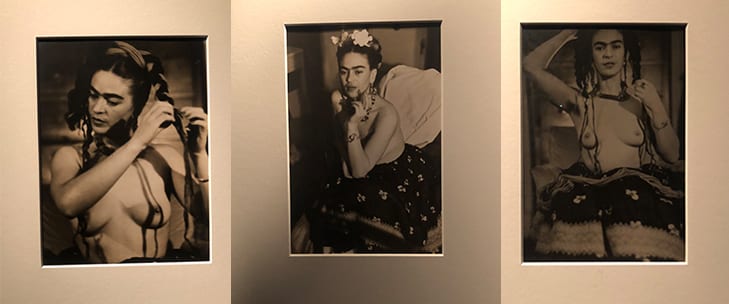

By late 1927, Kahlo was no longer on bed rest and she began socialising again and she joined the Mexican Communist Party (PCM). In June 1928 she was introduced to Diego Rivera and they soon began a relationship despite the 20 year age difference and having been married twice. Frida’s mother opposed the marriage and both parents refered to it as a “marriage between an elephant and a dove” due to to the couples difference in size. Regardless, her father approved of Rivera as he was wealthy and able to support Frida, who could not work and had expensive medical bills and treatments. In late 1930, the couple moved to San Francisco, where Rivera painted murals for the Luncheon Club of the San Fransisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts. Kahlo was introduced to American artists such as Edward Weston and Nickolas Murray, who she would later go on to have a long affair with. Pictured below is an intimate series of photos Murray took of Kahlo in New York.

Kahlo found living in the USA difficult, she disliked aspects of American society, which she regarded as colonialist. Her time there was also complicated by a pregnancy which resulted in a miscarriage and caused severe haemorrhaging. Although Rivera wished to continue their stay in the United States, Kahlo was homesick, and they returned to Mexico soon after the mural’s unveiling in December 1933.

Back in Mexico City, Kahlo and Rivera moved into a new house neighbourhood of San Angél. The bohemian residence became an important meeting place for artists and political activists from Mexico and abroad. Kahlo began experiencing health problems again — undergoing an appendectomy two abortions, and the amputation of gangrenous toes. Her relationship with Rivera also became strained as he was not happy to be back in Mexico and blamed Kahlo for their return. Rivera then began an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister Cristina, which deeply hurt Kahlo’s feelings. Frida moved to an apartment in central Mexico City and considered divorcing him but reconciled with both of them later in 1935. However by 1939, Rivera would ask for a divorce citing both their mutual infidelities.

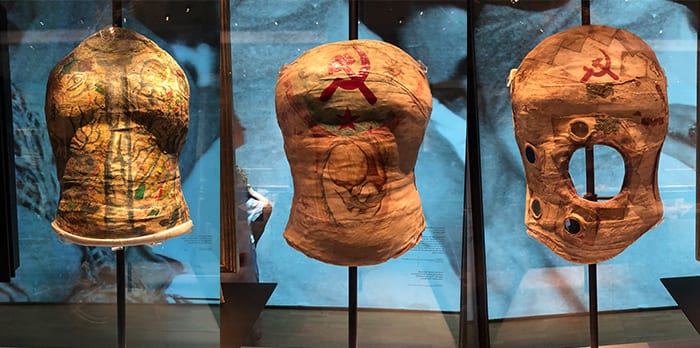

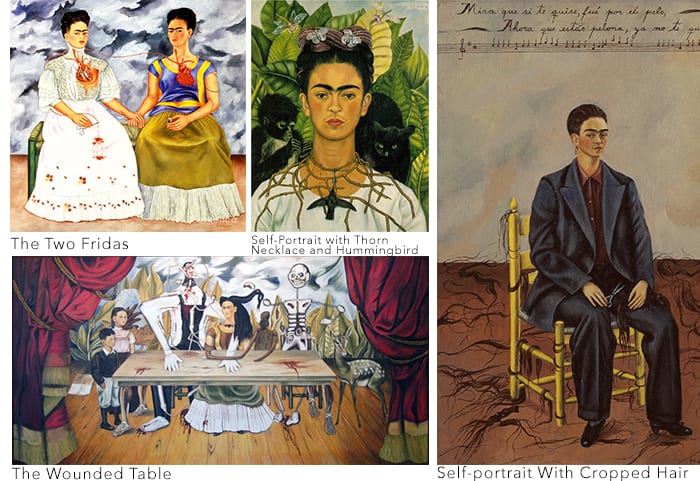

Following her separation from Rivera, Kahlo moved back to La Casa Azul and began another productive period as an artist. She painted several of her most famous pieces during this period (see below) and three exhibitions featured her work in 1940. Despite the medical treatment she had received in San Francisco, Kahlo’s health problems continued throughout the 1940s. Due to her spinal problems, she wore twenty-eight separate supportive corsets, varying from steel and leather to plaster. She experienced pain in her legs, the infection on her hand had become chronic, and she was also treated for syphilis. The death of her father in April 1941 plunged her into a depression and her ill health made her increasingly confined to La Casa Azul, which became the center of her world.

In 1953 Kahlo’s right leg was amputated due to gangrene, she became severely depressed and anxious, and her dependency on painkillers escalated. When Rivera began yet another affair, she attempted suicide by overdose. In her last days, Kahlo was mostly bedridden with bronchopneumonia, though she made a public appearance on 2 July 1954, participating with Rivera in a demonstration against the CIA’s invasion of Guatemala. The demonstration worsened her illness, and on the night of 12 July 1954, Kahlo had a high fever and was in extreme pain. At approximately 6 a.m. on 13 July 1954, her nurse found her dead in her bed. Kahlo was 47 years old. The official cause of death was pulmonary embolism although it has been suspected that she committed suicide by overdosing on painkillers.

Rivera stated that her death was “the most tragic day of my life”, died three years later, in 1957.